To feed or not to feed half of the world’s population

All over the world, farmers put manure on their crops, because fertilizer provides plants with all sorts of nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Farmers have been doing so for up to 8000 years, but since the beginning of the 20th century, man-made, synthetic fertilizers have helped secure food for a fast-growing world population. In fact, we’re now past the point of being able to survive without it. Only thing is, synthetic fertilizer has turned out to be quite the polluter and climate sinner, so what must be done to find our way to sustainable agriculture? How do we keep feeding the world’s population – without harming it, too?

You’ve probably heard of it – but you’ve probably also pretty much forgotten about its existence in between watering plants and moments of sudden reek in the countryside. Sounds familiar?

Most people do not spend much of their waken hours thinking about… fertilizer. Perhaps it’s often thought of as sort of a wonder cure to stagnant indoor plants, but synthetic fertilizer has been developing since the beginning of the 19th century – and not for the good of great, decorative, green parts of nature inside our homes.

Almost 8000 years ago, farmers recognized the value of fertilizer. So, while current fertilizer practices are relatively recent, traditional practices are ancient. In fact, it was initially believed that the concept was not more than 2000 - 3000 years old, but this has since changed to a belief that farmers used manure to fertilize their crops at least 5000 years before that, a team led by archaeobotanist Amy Bogaard from the University of Oxford found. “But how did they get the idea?” you may ask – and with good reason, since the practice is not the most obvious. But the answer is rather simple: Researchers have concluded that farmers must initially have noticed an increase in crop growth in areas with natural dung build-up.

Did we also use… bones?

We did – for a period of time. Ground-up bones from e.g. bison skulls also provided nutrients to crops around the world. And it wasn’t until after the German chemist Justus von Liebig (1803-1873) determined the essential elements to plant growth – nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium – that the first nitrogen-based fertilizer came around. Father of the Fertilizer Industry, Liebig was named.

Today, the Nobel prize-winning chemists Carl Bosch and Fritz Haber, who walked in Liebig’s footsteps, are widely known as pioneers within the field of ‘modern’ manure – after having found a way to transform nitrogen in the air into fertilizer. This ‘way’ later became known as the, now very famous, Haber-Bosch process.

A Norwegian piece to the puzzle

“And how is this a trace of North?” you may ask. Well, in 1903, the Norwegian industrialist and scientist Kristian Birkeland – along with his business partner and industrialist Sam Eyde – managed to produce nitrogen oxides from the air using electricity on an industrial scale. In short, they were first on nitrogen fixation, only their method was relatively inefficient in terms of energy consumption.

The invention though formed the basis for Norsk Hydro (later Yara International), founded by Birkeland and Eyde in 1905 – the world’s first producer of mineral fertilizers. In 1927, Norsk Hydro started using the more energy-efficient Haber-Bosch method, and the company has since produced synthetic fertilizers for billions worth and helped the world get more food.

Today, the Norwegian company Yara International – separated from Norsk Hydro in 2004 – is one of the world’s largest producers of synthetic fertilizers. And while the term ‘synthetic fertilizer’ does not necessarily have the most positive ring to it, here’s something to consider:

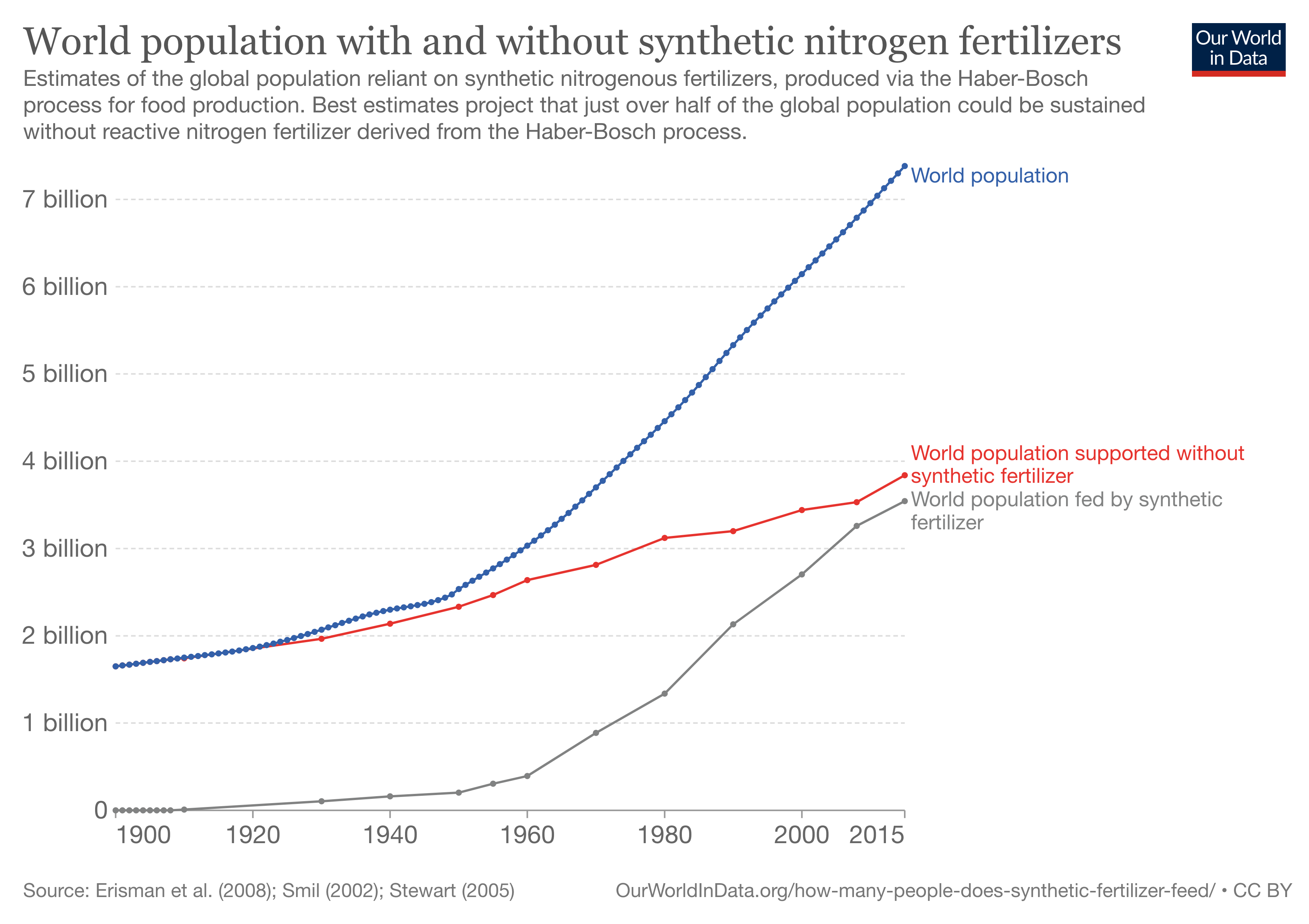

The world’s atmosphere is made of 78% nitrogen – in the shape of nitrogen gas (that plants can’t immediately utilize). It’s converted to more profitable compounds in the natural nitrogen fixation process, yes – but that’s not large enough to meet the need in our global agriculture. It is estimated that nitrogen fertilizer now supports approximately half of the global population – meaning that the pioneers of this technical breakthrough are estimated to have enabled the lives of billions of people.

It is estimated that nitrogen fertilizer now supports approximately half of the global population.

But is it even sustainable?

Kristian Birkeland (1867-1917), professor of physics at the University of Oslo, found a way to use hydroelectric power – renewable energy – in the production of synthetic fertilizer. And in the beginning, the Haber-Bosch method was based on renewable energy and raw materials, too. But then we, mankind, discovered natural gas, and “it’s crucial that we turn to producing fertilizer from renewable sources,” claims e.g. Norwegian professor in chemistry at the University of Oslo Truls Norby.

“It’s crucial that we turn to producing fertilizer from renewable sources"

And, as a minimum, it must be. While nitrogen is essential for life on Earth, and while fertilizer helps feed the world’s population, it’s also a huge contributor to greenhouse gas emissions – and during the last 100 years, the amount of man-made nitrogen compounds in soil, water and the air has doubled. An increase largely driven by the widespread use of synthetic fertilizers, and an increase pollutive to water, animals, plants, and humans.

Therefore, and not surprisingly, climate risk is at the top of a company like Yara International’s agenda. Together with Unilever, they helped found the Food and Land Use Coalition – a multi-stakeholder platform with a mission to transform agriculture and food systems into absorbing more climate-change causing gases than they emit.

And now. To answer the question previously raised: No, it’s not sustainable. No, we cannot not come up with a better solution. But yes, we did feed – and currently continue to feed – billions of people through synthetic fertilizers.

Though we’re not there yet, much needed solutions are in sight and are being developed. And just like that, one – at the time – extraordinary innovation might turn out to be fertile soil for another.

So, what’s it going to be?

A little more info

-

Fertilizers: challenges and solutions by UN environment programme

-

Yara’s mission to bring climate-smart agriculture to Africa's smallholder farmers by Reuters Events

-

How many people does synthetic fertilizer feed? By Our World in Data

-

The future farmer will make synthetic fertilisers at their own farm by University of Oslo

-

Stanford study: High-yield agriculture slows pace of global warming, say Stanford researchers